One of the first sketches I ever wrote for The State –I was probably about 17 – involved a couple boys playing Star Trek on the local playground. After a bit, two neighborhood girls approach and ask if they can play, too. There’s some back-and-forth and then two of the kids depart, leaving one of the boys and one of the girls alone. They end up swinging on the swings and having a sweet conversation about something or other, I don’t remember what. Basically, it’s about two children falling in love.

For years, this sketch embarrassed me: too earnest, too gentle. Back then, we were trying to find our voice as a group. This sketch was everything we were not. Even in those early days, The State was aggressive, loud, edgy (whatever that means). “Playground” could not have been further removed from the group we were becoming. Yet that sketch keeps returning me to, decades later, as a totem of where I sometimes feel like I took an unfortunate detour as a writer and artist

Why did I have no room back then for gentle and earnest? Why did it take until middle age for me to allow space for those softer qualities? I suppose it’s no coincidence that our almost entirely male group would gravitate towards our in-your-face, punk rock approach to comedy. And I suppose it’s no coincidence that the years of our formation and maturation as comedians – the late 80’s and early 90’s – coincided with the ascendent conservative backlash towards the sexual revolution and the burgeoning gay civil rights movement in the face of governmental apathy towards the AIDS crisis.

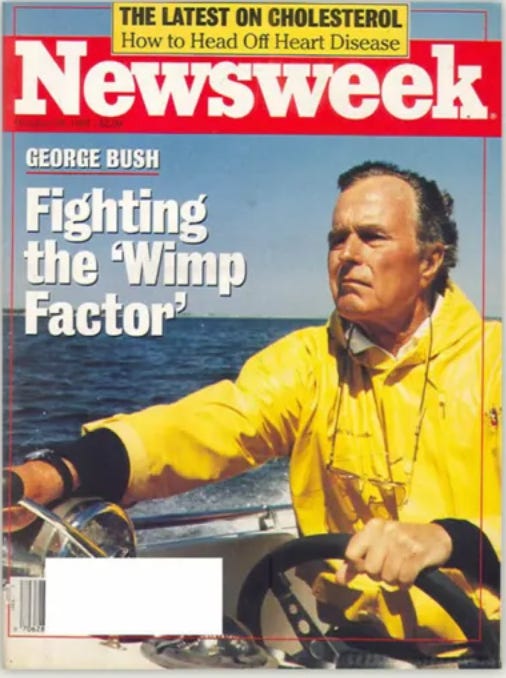

To be gentle was to invite ridicule and scorn. Kind men were weak. Sweet men were targets. When the first George Bush ran for president right around the time I wrote “Playground,” I remember a famous Newsweek cover featuring Bush piloting a speedboat with the headline, “Fighting The Wimp Factor.” If George HW Bush, decorated World War II naval pilot, vice president, and former head of the CIA, was too “wimpy,” what was I? I knew already, having suffered the indignities of high school in New Jersey. I was a - to use the word hurled at me on an almost daily basis – fag.

Anything that provoked the kind of “awww…” response we got from “Playground” invited the kind of unwelcome attention I pretended I was too cool to let bother me. But I wasn’t, and it did. My rebellion against the conventions of the day ended where teasing began.

The stories we tell ourselves about ourselves are often laughably wrong. Mine was. I thought of myself as edgy, outspoken, unafraid. The truth could not have been more different. In my heart, I was domestic, soft-spoken and terrified. When I was with my mob, I could be the person I pretended/wanted to be. Alone, I was none of those things. Alone, I was the person you read in these pages: sentimental to the point of mortification, literary, and more often than not, black of mood. Alone, I was the kind of person who would sit down and write a sweet sketch about two children flirting on playground swings. No wonder that sketch haunted me. It was everything about me I was trying to conceal.

No matter how often I told myself that I could become the man of my imagination, I could not. The Wimp Factor was strong with me. Not just because I had little to no physical strength, but because I was did not have the fortitude to love myself for who I am. That’s what I’m trying to set right now. It’s why I wrote my last book, A Better Man: A (Mostly Serious) Letter to My Son. It’s why these essays are rarely as sardonic as I am sometimes on stage or on television. It’s why I now try to keep my heart soft and pliable. It’s why I now fuck men.

(That’s a joke.)

(But the joke is a reversion to the sort of thing I might say to raise my shield of immunity against my high school tormentors, and for the thirtysomething years since. And it’s the kind of joke I am trying to get myself out of the habit of reflexively making.)

(All of that being said, it’s pretty funny.)

Not sure why I thought of that old sketch this morning as I was sipping my breakfast tea. Maybe because this Substack has real value for me as a place of authenticity; even if I didn’t want to admit it to myself, that sketch was truer to my nature than 90% of what I wrote in subsequent years. One of the reasons our contemporaries and sort-of rivals The Kids in the Hall are so good is because they didn’t fall for any of that macho crap that we exuded. I mean, they’re Canadian so maybe they’re incapable of machismo. Maybe it’s why I am so often confused with them. “Loved you in Kids in the Hall,” people say to me all the time. To which I reply, “Thank you.”

I always thought the mistake happened because I look like a mélange of them if you squint your eyes and don’t know either group very well. Or maybe, I thought, I just give off a Canadian vibe. But now I wonder if it’s something else. I wonder if people recognize something in me I was afraid to acknowledge in myself all those years ago. Maybe they think I’m in Kids in the Hall because it’s a more natural fit for me than The State. Shit, maybe I should join Kids in the Hall.

Nobody is any one thing. We are all every thing. We are all, each of us, sentimental, no-nonsense, kind, malicious, soft of heart and hard of head. We are all all of the things. Those upset by “wokeness,” and the lessons of humility and vulnerability it brings might consider the various ways they too have sublimated themselves in favor of the status quo, no matter how ugly and abhorrent that status quo may be. When we wake, it is from sleep. We wake from one world to another. Our job is to make the world in which we wake the best it can be. Sometimes that means swinging a sledgehammer, but sometimes – most times – it just means demonstrating quiet kindness. The kind of small, almost invisible kindness you might see between a boy and a girl swinging on swings together at the local playground.

Two posts in as many days... one might think you’re back here in Redding CT snowed in with the rest of us. If so, LMK. We can cuddle.

This is probably one of my favorite things you’ve written here. Thank you for sharing, Michael.