How is it that we can live in this world all of our lives and leave having understood almost none of it? I’m not planning on dying anytime soon but I suspect when I do go, it will be with only slightly ignorance than with which I arrived. C’est la vie, I suppose, although that phrase is usually uttered with a resignation to endure life’s various vicissitudes. I mean it differently – not that we are consigned to our own stupidity but that our stupidity and our flailing attempts to escape it are, in fact, the whole point of life. Such is life. In that sense, our ignorance is our greatest gift because it gives structure and meaning to our species. After all, so far as we know, we’re the only ones who feel this way. No other species on this planet wakes up wondering about their purpose. Cows, for example, almost certainly do not experience ennui.

All of that to say that I am woefully ignorant of almost everything, which is actually kind of a delight for me because I always have something to do; my latest project (in addition to learning algebra), is trying to figure out how to use the I Ching, or the Book of Changes. Probably like many of you, I had heard of the I Ching, but never thought anything about it. Then, when wandering through one of my favorite Savannah bookstores, The Book Lady, I saw the 10th anniversary edition of Tao Master Alfred Huang’s translation and thought, well hell, something is calling me to this. So I bought it and I’ve spend the last couple of weeks trying to figure out what to make of it.

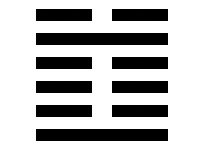

The Book of Changes is, indeed, a book. It is also an oracle and a psychotherapist and confidant and handbook for living. What became the I Ching was first begun almost five thousand years ago by the mythological Chinese sage Fu Xi, who wrote down the first eight trigrams of the I Ching. A trigram is just what the name implies, three lines a bit like Morse Code. The lines lie atop each other in a series of long lines (yang) and short, broken lines (yin). The original eight trigrams represented Sky, Earth, Thunder, Wind, Water, Fire, Mountain, and Lake (I don’t know why “lake” gets a separate trigram from “water” but there you have it.)

Centuries later, King Wen combined the trigrams to create 64 hexagrams, lines of six, and wrote interpretations of the new forms. His son, the Duke of Zhou, wrote further commentaries. Centuries after that, Confucius added his own commentary to the commentaries, which are known as “The Ten Wings.” Taken together, these four sages created the I Ching, in a similar way that the Holy Bible is written by many authors over much time.

There are many methods for accessing the wisdom in the I Ching but the two most common are a method involving fifty yarrow sticks, which are plentiful in China but not so much here. This method requires manipulating the yarrow sticks in such a manner to create each line of the hexagram or gua. The more common method in use today is the throwing of three coins. Each throw creates one line. Six throws create a hexagram. Once the gua is determined, the petitioner finds the associated hexagram in the I Ching, possibly along with an inverse hexagram (depending on the throw) to figure out what answer the book is giving. It is up to each reader to interpret the reading in the manner they feel best resolves their question.

Those are the basics, and I cannot explain any further because I do not understand beyond this, but it gets very intricate and involved. So, the question: does it work? People around the globe seem to think so, including Carl Jung, who spent a great deal of time working with the I Ching and wrote:

I have no answer to the multitude of problems that arise when we seek to harmonize the oracle of the I Ching with our accepted scientific canons. But needless to say, nothing "occult" is to be inferred. My position in these matters is pragmatic, and the great disciplines that have taught me the practical usefulness of this viewpoint are psychotherapy and medical psychology. Probably in no other field do we have to reckon with so many unknown quantities, and nowhere else do we become more accustomed to adopting methods that work even though for a long time we may not know why they work. (Italics mine)

Of course, hundreds of millions (billions?) of Chinese have also believed in the book’s powers, and, as the saying about another popular figure goes, 50,000,000 Elvis fans can’t be wrong. Or can they? I haven’t attempted to use the I Ching myself because I want to approach the book with as much respect as I can before trying it out, which means learning as much as I can on my own before taking it for a test drive. Many scholars on the I Ching advise that the book must be approached with, above all else, sincerity. If I am going to use it, I want to be sure that I am sincere in my attempts.

Until fairly recently, I would have dismissed the I Ching (along with tarot, astrology, Ouija boards, etc.) as superstitious nonsense. Mao Zedong thought along the same lines, banning the book and its associated religion, Daoism, during various periods of his reign. He may as well have tried to stop the flow of the Yangtze for all the good it did. Although the number of Daoist monks decreased by as much as 90% during Mao’s reign, the I Ching remained in circulation. In fact, the translator of my edition was jailed for many years because of his involvement with the book. If somebody is willing to be imprisoned for his beliefs, who am I to dismiss those beliefs out of hand?

Lately my convictions in all things have grown much more porous. Why have oracles persisted across cultures and time? Why do so many people believe in such things? Where does the rational end and the irrational begin? How do we know when we have crossed the bridge? Or is the bridge itself a mirage and the strange lands we find ourselves traveling are all one sprawling continent? And what if our explorations have hardly begun?

I don’t know what to make of the I Ching. Lately, though, I don’t know what to make of anything. How is any one person supposed to make sense of anything in a single lifetime? Maybe there are multiple lifetimes. Until the last few years, I would have dismissed that possibility as well. Today, with my life (probably way more than) half over, I fear I have only grown dumber. I take comfort in the following quote from Confucius, who wrote, during his 70th year, the epigram which begins the Huang edition of the I Ching:

If some years

Were added to my life,

I would dedicate fifty years

To study the Book of I (the I Ching),

And then I might come

To be without great fault.

You can argue with Confucius and King Wen and the Duke of Zhou and Fu Xi and 50,000,000 Elvis fans, but I prefer to be like the placid cow. I will chew and chew, and if some years were added to my own life, I would use them to consume evermore grass. Perhaps the cow feels no ennui because it already knows everything it needs to know. If only people were so lucky.

This makes me curious about the I Ching. Tarot has rich symbolism that makes for hearty introspection. At the end of the day, they’re reflective tools to help us converse with the big I AM mirror.

" Cows, for example, almost certainly do not experience ennui."

Enough said.