Vibe Shift Part II

Wake Uuuuuuuuup!

In my last post, I put on my speculatin’ hat and poured myself a tall glass of “I don’t know what the fuck I’m talking about.” This post will continue down the same drunken path, knowing that much of what I ruminate upon is a combination of confirmation bias, wishful thinking, and the full intellectual heft of a man whose first professional credit was “Joez Diaz, Puerto Rican street hustler” on an episode of NYPD Blue.

Be that as it may, I would like to reference the great Stephen Colbert who once blurbed my first book with this quote that I wrote on his behalf: “Michael Ian Black has proven that even the most simple-minded among us can occasionally produce works of genius.”

(Yes, I wrote that and he graciously affixed his name to it because what’s going to do – actually read my book? Grow up.)

If you’re sensing a touch of insecurity on my part when I write about weighty-ish topics, it’s because I have no confidence in anything I’m writing, but I am convinced enough that there’s something to it that I’m willing to make myself look like a fool on your behalf. If that’s me a hero, then goddamnit, I’m a hero.

The nature of my speculatin’ involves a nascent effort to tie our current political moment to a vague sense of mine that we’re collectively witnessing and participating in an upheaval of thought that has the potential to reshape everything in a similar way that the Enlightenment threw off the shackles of everything that came before it.

The Enlightenment emerged in the early 17th century as a multidisciplinary reassessment of the world order, usurping religious dogma with reason and logic. God’s rule on Earth was overthrown in favor of the individual man’s faculties to question, test, measure, and hypothesize. (And yes, it was almost all men in the 17th and 18th century. Women weren’t even invented until 1793),

It is to the Enlightenment that we owe our modern age of satellites and smart phones and Pop Tarts. It is to the Enlightenment that we owe our entire way of thinking of the world as a primary physical place, a world that is, ultimately, knowable if enough intellectual rigor is brought to bear upon it. From there, the dominance of religion as the driving force of everyday life eventually ceded to the dominance of rationalism; if something cannot be tested, it cannot be said to be valid. Whatever cannot be falsified cannot be called “true.”

This is the basis for the Scientific Method, which has proven to be one of our more successful methods. Certainly more successful than the Rhythm Method, which we were warned against employing in high school sex ed. Where the Scientific Method fails – or at least where it has failed to this point – is in attempting to measure those experiences which are subjective and/or which are not replicable.

How do we measure the taste of strawberries, for example? How do we repeat the experience of seeing a ghost? How many of us have invalidated our own anomalous experiences because they are “impossible”? The Enlightenment was a profound awakening for the human species but, it increasingly appears, an incomplete one.

Roughly at the same time that Kant was writing, the first and second of four “Great Awakenings” were beginning in America. These religious revivals focused on the individual’s obligations and relationship to God. Deviating from much of the accepted wisdom of the day, the movement decreed that one’s interplay with the divine need not be mediated by the clergy. Indeed, dogma might be holding back salvation because ritualized worship undermines the personal freedom necessary to make the choice to devote themself to God.

Again, the imagery is that of rousing oneself from slumber. Such sleep can be interpreted as either naturally occurring or forcibly. Forced “sleep” may be imposed by powerful people or institutions who wish to keep their subject “in the dark,” as when American slaves were denied the ability to receive an education. Enforced ignorance was said to benefit those for whom it applied because it prevented those to whom it applied from “getting any ideas.” When we say “ignorance is bliss,” we have to ask for whom is such ignorance blissful?

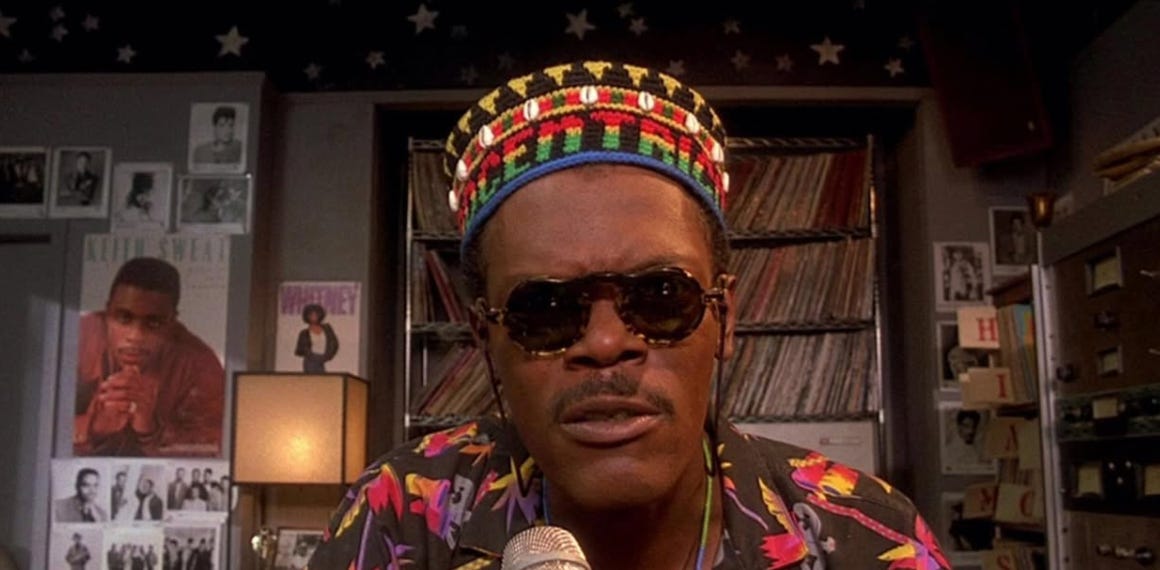

That enforced ignorance, and the systems erected to police it, eventually led to the concept of “wokeness” and its association with emancipation. In its current incarnation, that word - woke - seems to have grown out of its use in the labor movement, which asked workers to “wake up” to abuses being perpetuated by employers, and from the 1928 song “Sawmill Moan,” by Ramblin’ Thomas, although a lot of people credit Lead Belly for using it in a more pointedly political context in his 1938 song “Scottsboro Boys.” The word gained traction as a warning among black travelers to “stay woke.” Spike Lee eventually began his 1989 masterpiece Do The Right Thing with the line “Wake uuuuuup!” And then, of course, Black Lives Matter happened and you know the rest.

Again and again, in various human endeavors, we use the image of “waking” as an active way to translate ignorance to knowledge. We are thought to be asleep, which is to say unconscious, and then to be awake, which is to say conscious. In this context, consciousness is almost analogous to freedom. Without the expanded awareness that comes from awakening, we’re left without enough information to act with intention. If we are unable to act with intention, we cannot be said to be free. Waking up, therefore, is giving us the ability to operate within a higher level of freedom.

At the same time, we deploy sleep imagery as a way to activate the imagination. “To sleep, perchance, to dream,” as Weird Al Yankovich once sang. And in dreaming, to envision some new avenue of exploration. “Dream big,” we say, which implies a rejection of the rational in favor of the exuberant. Or “dare to dream,” which suggests that our potential is greater than we’ve been led to believe in our rational world.

It's a funny, but telling, quirk of the language that even in our Age of Enlightenment-derived times, we still call upon dreams and the unconscious to point us towards greater enlightenment. We seek the dark in order to find greater light. It’s as if we’re telling ourselves that there’s much to be gained from the unseen, the shadowed and obscured.

Maybe another way to think about this is to consider the nature of constraint. The rational world, the world of logic and reason, is entirely about limitation. What is science if not defining boundaries? The dreaming world is about removing those bindings. We are imaginative creatures. When we activate our magical thinking caps, we grant ourselves permission to envision potentialities, whether they are “possible” or not. For example, I have no trouble envisioning my current screen crush, Keira Knightley, and I sharing a bubble bath. On a distant planet. In, say, 1530. Is such a thing possible? I choose to believe so.

Unlike Kant or Spike Lee, I’m not certain that the waking world is more “real” than the dreaming world. In fact, if you listen to the stories of near-death experiencers, they often discuss how their NDE seemed “more real than real.”

Upon “returning to their bodies,” they try to describe a level of reality that they claim is sharper, brighter, and infinitely more beautiful than anything we have here. How can a brain create a level of reality that surpasses our own? Because wouldn’t such a “hyper-reality” have to exist outside of our own, more prosaic one? How do we experience colors that we’ve never seen before (which is a common facet of the NDE)? It’s as if our reality is a scaled-down projection from a higher reality, the same way a televised football game does not have the same fidelity as seeing it in person, no matter how good you’re television set.

How does any of this relate to our current political movement? I have some ideas, which I will continue to explore in future posts. To finish up today, though, I would simply note that historians don’t agree with exactly when the Age of Enlightenment ended or exactly why, but many point to the French revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars as its conclusion. Odd. It seems as though rationality and reason can lead to instability and massacre just as readily as myth and superstition. It is entirely possible, as we head into the coming years, that we will allow our ever-so-rational works to destroy us. Stay woke.

I like your musings; write on. I infinitely prefer my dreams to reality. Unfortunately I can’t live there.

I too think we are in the middle of a massive societal change. Humanity is at a critical inflection point. Between AI and potential NHI, ramping up global tensions and climate change disasters, the next few years/decades are going to be nuts.