The baseball playoffs are here and I confess I have almost no idea what’s happening. All I know is the Yankees and Mets both made it to the post-season, which for a New Jersey kid like myself is pretty good.

As a boy, I loved baseball, both watching and playing. One of my earliest memories is sitting, by myself, in my parent’s bedroom watching Reggie Jackson bat during a Yankees post-season run. I remember the duelling senses of calamity and elation with each pitch. Strike one, ball one, a foul tip for strike two. An entire opera from the moment the ball left the pitcher’s hand to the time it crossed the plate.

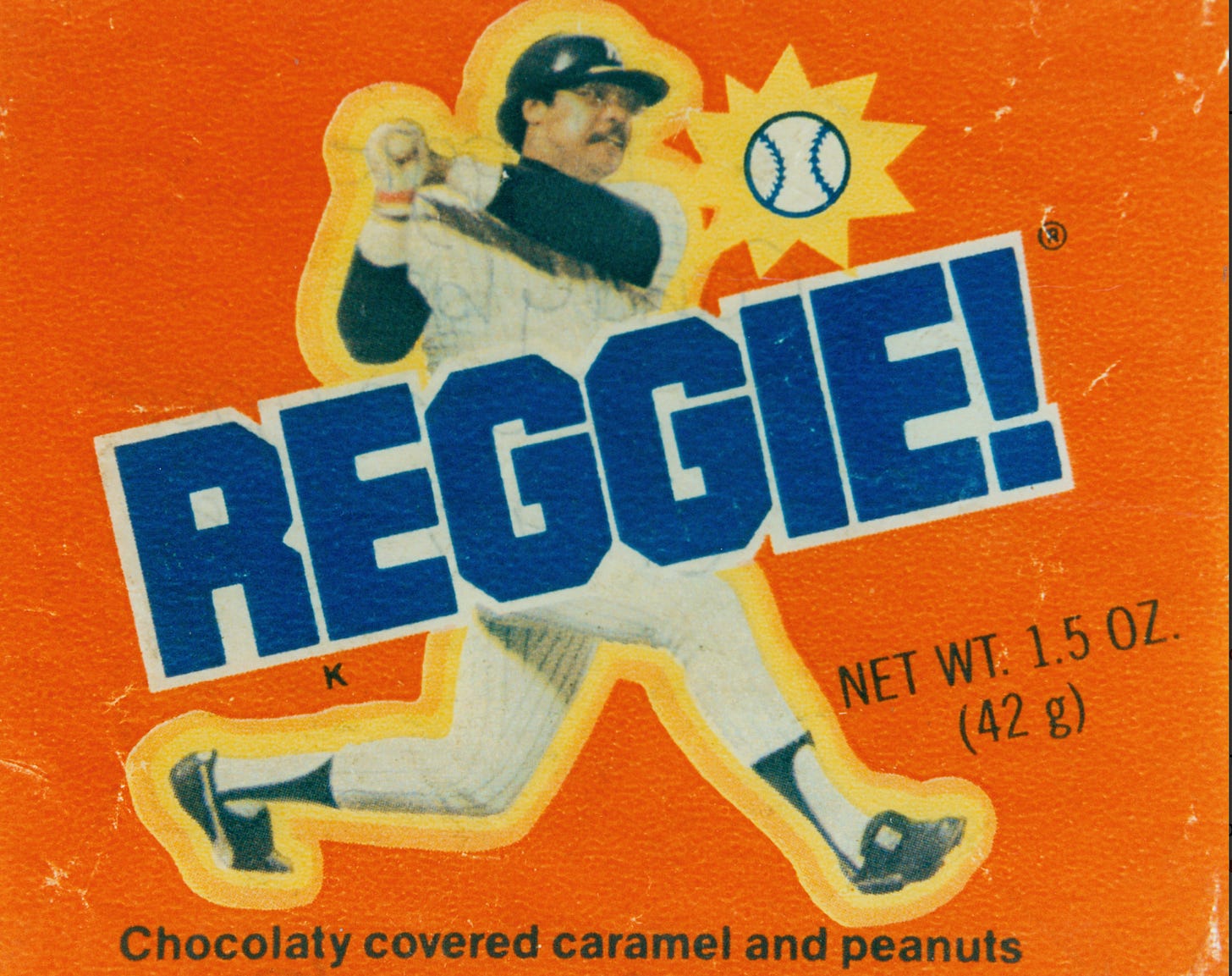

To a kid, a sports stars are indistinguishable from gods. They were, if anything, more powerful than the gods of my upbringing. After all, Reggie Jackson had an entire candy bar named after him, which seemed as miraculous to me than turning water into wine.

God didn’t have His own candy bar.

It never occurred to me that professional baseball players were just guys in their 20’s and 30’s, young men only slightly removed from the guys who pumped gas at our local filling station. Had I met one in person, I think I would have been too awestruck to speak, the same way I was when I met Robin Williams years and years later. Some people, I thought, were just better. At the time, I didn’t know who the X-Men were, but that’s how I imagined them. Mutants with extraordinary powers. Part of me still does.

I’m trying to think if I would have considered those guys “heroes.” Not exactly, I suppose. I didn’t think of them as heroic so much as just special, chosen. Or maybe, “destined” is a better word. There were people out there who had been touched by greatness. Kids my own age, somewhere, who would one day put on a Yankees uniform and run across the perfect green grass in the House that Ruth Built.

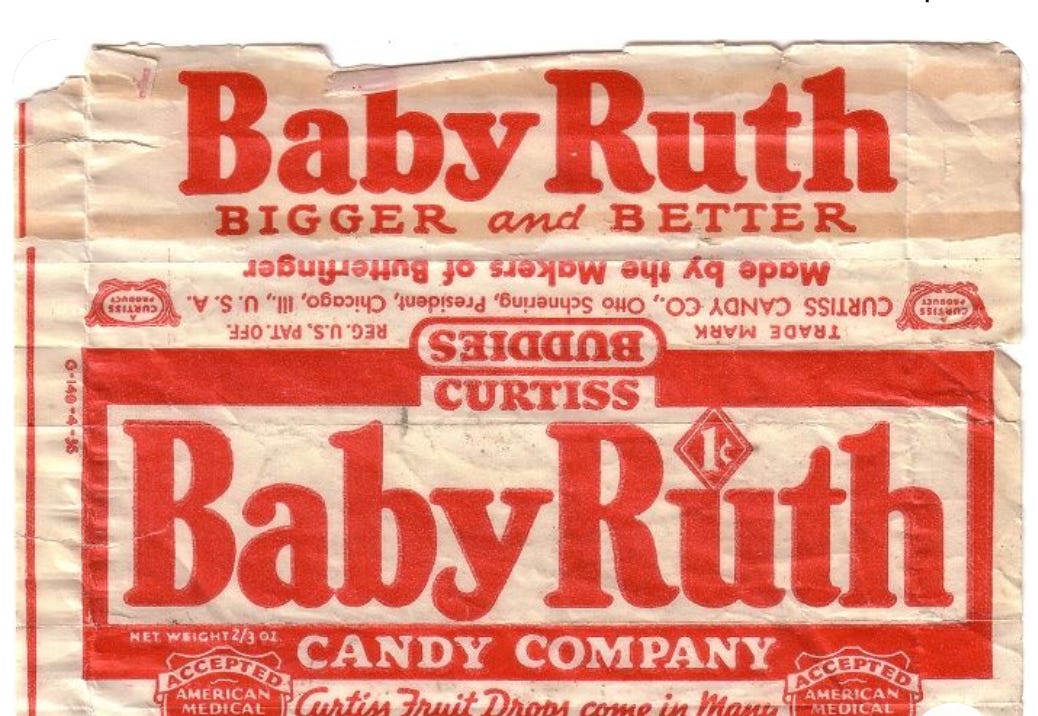

As a kid, I spent a lot of time thinking about George Herman “Babe” Ruth. He, too, had a candy bar named after him. (Or so I thought; the Baby Ruth candy bar was actually named for Grover Cleveland’s daughter, Ruth, but I didn’t know that then and don’t particularly care about the truth of the matter now. I will always associate it with Babe Ruth and I think you should, too.) Babe was a street kid who grew up in Baltimore, Maryland. “Incorrigible” is how his behavior was described, until a local priest gave him a baseball bat and told him what to do with it. From the start, he was a natural, as good a pitcher as he was a hitter. To this day he’s considered one of the game’s great left-handed pitchers.

He was the first person I ever heard associated with the phrase “larger than life,” and though he was long dead by the time I came along, he was as present for me in my daily life as Paul Bunyan and Davy Crockett, mythic American figures whose lives were some pastiche of the real and imaginary. There was a story that Paul Bunyan was so fast, he could blow out a candle on one side of the room and be in bed before the flame was extinguished. If you had told me the same thing about Babe Ruth or Reggie Jackson, I would have believed it.

I signed up for Little League as soon as I was old enough. I was a fair player, nothing special. In my mind, though, I was on track for the Majors, just as every nine-year-old is on track for the Majors. Each game felt life-or-death, and I remember my mother admonishing me to stop crying after every loss. “It’s just a game,” she would say. But it wasn’t just a game to me. I bundled my entire sense of self into those abridged six inning games. Baseball gave me purpose and identity, so much so that, to this day, I still remember sprinting across center field towards right, and diving to snag a long fly ball hit by an opposing player. I remember the feel of the grass underneath my feet and the surety I felt that I could make the grab. I remember the feeling of the ball hitting my glove and, upon standing up, holding the glove aloft to prove I had caught it. It’s among my most vivid childhood memories.

There isn’t anything special about baseball itself. Kids around the world feel the same about soccer and cricket and Formula One. They put their dreams into these sports because dreams need some sort of basket to keep them safe. Sports have a reliability about them. They’re order-based and easily understood. At the end, a winner is declared. Afterwards, the world resets itself in preparation for the next contest. Life, it seemed to me back then, was a series of unimportant events between at-bats.

My sister Susan has Down Syndrome, and much of my early childhood was spent trundling from doctor’s appointment to doctor’s appointment for her. My parents fought a lot, and then they divorced. My brother had surgery to correct a cleft palate. I was the middle child, bereft of medical problems that would have afforded me much-needed attention from my mom. My childhood is not much more than a blur of Kodachrome slides, none of them particularly inspiring.

During baseball season, though, I could be inspired. When Reggie was at the plate. Or Thurman Munson. Or Ron Guidry closing out a game. Chris Chambliss out in center field. Their volatile manager, Billy Martin, barking from the dugout. That life, the life of a baseball team, was more real to me than my own. That was where I lived, up in the Bronx with my guys instead of in the crummy New Jersey townhouse I shared with my brother and sister.

Only a couple years later, I ditched baseball for theater. My mom had given me the choice – one or the other – because she didn’t have time to chauffeur me to both. I chose to give up one dream for another. Baseball for Broadway. In retrospect, it was a good decision. I was never going to be a Major League baseball player. I never made it to Broadway, either, but I somehow figured out a way to turn a dumb kid’s dream into a career.

Every now and again, though, when the postseason starts, I do feel a twinge of regret. Not that I didn’t pursue baseball further, but that I allowed the magic to dissipate. I suppose that’s inevitable with age. The older we get the clearer we see the illusions. The twinge, then, is for a child’s ability to believe in magic at all. Maybe it’s why I felt so sad when the disgraced Pete Rose died this week. Eighty-two years and never stopped believing in the magic of baseball, long after baseball had stopped believing in him. Sports have the unique ability to make magic real.

I probably won’t watch a single baseball playoff game this year. Won’t watch the World Series, either. But I remain grateful for what baseball did for me when I needed it and I will always feel affection for the now much-younger men whose job it is to step onto those perfectly groomed grasses and inspire kids to dream.

Aw, Michael, watch the games. Watch one or two. The magic is still there…..

This was terrific. I have a goal to visit all 30 MLB stadiums and knocked out both Camden Yards (Baltimore) and Citizens Bank Park (Philadelphia) the last week of the season on back to back days. They both provided such unique experiences, yet there was that buzzing energy throughout that was so cool to see.

I haven't kept up with baseball as much either, but you nailed it: there's a magic within the sport that really helps us as kids, and we can only hope to hold onto it in adulthood.