I changed my name. I was born Michael Ian Schwartz. but changed it to Michael Ian Black when I was around 19. The name change has always been a source of some small shame with me, even though the name I choose is just a translation of the name with which I was born. In fact, there’s a sketch I wrote for the show The State in which I introduce myself saying, “Hi, I’m Michael Ian Black. But my real name is Michael Schwartz, which I changed because I am ashamed of being Jewish.” It’s a joke, but there’s also an element of truth behind it.

First of all, let me state, unequivocally: I am a Jew. I don’t practice the religion but I feel my Judaism down to the tip of my circumcised schmeckle. There’s much about Judaism to love and from which to derive pride: the long history, the tradition of scholarship, the fact that Paul Newman was one of ours. But, especially for the immediate generations preceding mine, there is also a lot of pain and guilt, epigenetic trauma from a historical event that, even growing up in the 70’s and 80’s, still felt fresh.

For my parents’ generation and their parents’ generation, the second world war and its attendant horrors for the Jewish people remained an open wound. It wasn’t just the genocide but also the world’s indifference to Jewish suffering. During the war, America did almost nothing to help Europe’s Jews, even turning away a ship containing 900 Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis. The passengers of the M.S. St. Louis were also refused admission in Cuba and Canada before the ship was eventually sent back to Europe, where about a third of the passengers would be murdered in concentration camps. The message was clear to Jews: the world does not care about you.

(The same message has been learned again and again by refugees from across the globe during subsequent periods of warfare and instability; the world does not care. It is also the reason I am so vocal about my support for refugees.)

My family was already in the States, most of them having emigrated during the first years of the twentieth century, around the time Russia’s anti-Jewish May Laws were enacted, making life nearly impossible for the many Jews who had settled there over the centuries. Both my mother’s and father’s people came over during this period, my mother’s side settling in Chicago, my father’s in Queens, New York.

That’s the history Michael Schwartz and the American Jews of my generation were born into; it’s a history of survivor’s guilt and the concern that such a thing could happen again. Jews my age that I’ve spoken to about this all understand the feeling of keeping a bag packed, just in case.

It’s this uneasiness with the world around us that provokes many Jews to keep their heads down and assimilate. That assimilation is supposed to offer protection. If we make ourselves useful – even invaluable – perhaps the next time an antisemitic fever breaks out, we will be inoculated. To a certain extent, that strategy has worked. Jews are a tiny minority in the United States, less than two percent of the population, but our contributions to this nation have been mighty. We have fought for our place here and have done as much as anybody to make this nation great. Even if that were not the case, it shouldn’t matter. One should not have to justify one’s existence as a citizen by the contributions one has made, either as an individual or as a group. Regardless, despite some persistent (and growing) antisemitism, American Jews have made successful lives for ourselves here.

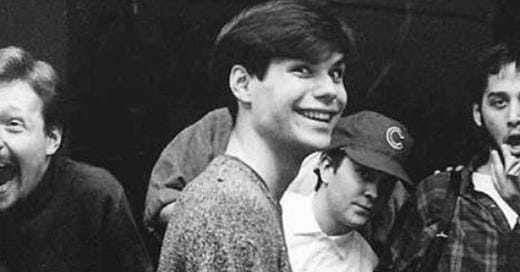

When I decided to become actor as a teenager, I knew almost nothing about show business. I certainly didn’t know any other actors. I knew there was a long tradition of “stage names” which were used to make actors sound more… something. Americans back then seemed to prefer their movie stars to be of generic WASP stock. Would Marion Morrison ever have become John Wayne without the name change? Would Issur Danielovitch Demsky ever have become Kirk Douglas? Would Betty Joan Perske have found love with Humphrey Bogart, or did he need her to be Lauren Bacall? I don’t know. What I knew was that the odds were stacked against me, as they are against any actor, and I needed to do everything I could to give myself the best chance to succeed.

One way to do that would be to shave off any obvious ethnicity. “Michael Schwartz” was obviously Jewish, but Michael Ian or Ian Michaels or Michael Ian Black could be anything. The idea of being anything appealed to me as a young actor, but also as a young Jew unsure of himself in the larger world that awaited him. When I walked into a room to audition, I just wanted to be a blank canvas, a person of indeterminate ethnicity, which would give me the greatest opportunity to play the greatest range of roles. And it wasn’t like the world was going to run out of Schwartzes.

So I changed my name.

I remember telling my mom about my decision (my dad had died several years before). I don’t remember how I explained the decision, but she didn’t push back too much, even suggesting a couple ideas for the name I could choose. Even so, I felt uneasy about my choice, perhaps the way anybody feels when they obscure their true identity. It took years for “Black” to feel like my name; maybe not until I was able to give my own children the name did it really feel like me.

Names are powerful incantations. All of our associations with that person are entwined with their name. To speak somebody’s name is, in some ways, to speak them into being. When I write my father’s name, Robert Michael Schwartz, I almost feel like I conjure him into being. There he is: his thin smile, the white t-shirt he used to wear around the house, the ridiculous teddy bear baseball cap his second wife gave him the Christmas (she was Christian and he didn’t care about Hanukkah) before he died. But it’s not the name that makes the person. Rather it’s the person that makes the name.

If I had to do it again, I don’t know if I would change my name. I definitely prefer my new name to my old. “Michael Ian Black” just sounds snappy! And I think my wife prefers being Mrs. Martha Hagen-Black to being Mrs. Marty Schwartz. Much hipper. At the same time, I’m not sure it’s worth the lingering guilt I experience all these years later, guilt which feels particularly acute when Jews are back in the news, as they are now with the horrendous situation in Israel. Anyway, now is probably a good time to let you know that I will be changing my name again, this time to Michael Ian Mellencamp

.

I'm so enjoying your substack! I discovered you while watching Celebrity poker many moons ago:) Great to catch up with what's happening in your world! Your perspective resonates with this almost 70 year old woman. Probably not the target audience you were hoping for but I'm here:)

Hi Michael. It's obvious that you are proud to be Jewish, just like me. My last name isn't obviously anything, so that's never been an issue for me, but as an actor and comedian I know that at times I have been passed over (like the holiday) in favor of a gentile, just because someone in the room didn't like Jews.

I'm also a strict, practicing Jew, and wear a yarmulke all the time, so that makes me very obvious, even if I'm not running into a deli or the local synagogue.

I mention all this because everyone looks at me at times like this, like I am the spokesman for Jews, Judaism, and Israel, and of course I am not. But I do try to be an ambassador of sorts, to explain to those who ask, what's going on in the world with regards to antisemitism (which is alive and well, unfortunately), the double standard to which Israel is held on the world stage, and any other thing touching Jewish traditions, thought, writings, and every controversial thing connected to Jewishness, which is everything (except Paul Rudd. Everyone loves him.)

I hope you can use your platform to dispel myths about Jews and Israel, and I am proud to call you my brother, as all Jews are family. Praying that you, your family, and all our people will be safe, with God's loving protection.

Markus Kublin,

but really Menachem Mendel Aharon Kublin, son of Laib Moshe the Levite