Now I’m on double strike. The writers’ union hit the picket lines ten weeks ago and today the actors follow suit. I haven’t said very much about either union because, frankly, I don’t understand the issues well enough to have an opinion on the minutiae of streaming service residuals, AI, and the slow degradation of our abilities to earn a solid living due to corporate consolidation and general corporatist malfeasance. But I do know this: I am pro-union.

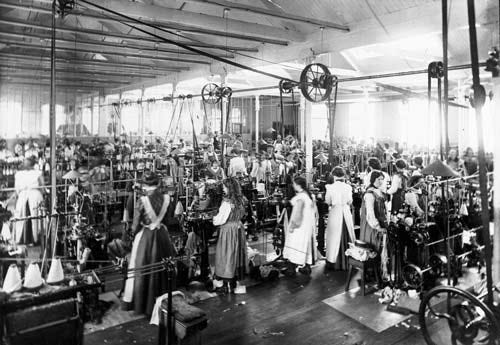

Unions have been the single greatest asset workers in every industry have ever had. The modern union movement began in the mid 19th century, both in Great Britain and the US. This was smack dab in the middle of the Industrial Revolution, when working conditions were abominable: 12 to 14 hour working days, low pay, lack of safety, no mandated sick or vacation days, etc. Workers were at the mercy of their employers, who had no particular incentive to treat their employees well. It’s rarely a good situation when safety and fair pay depend on a factory owner’s humanitarianism.

Eventually, the workers had enough. They organized. They were met with violence, conspiracy charges, threats, intimidation, loss of livelihood, loss of life. They kept at it. Eventually, British unionism was recognized in 1871 with the passage of the Trade Union Act. In the US, things moved a little more fitfully until 1886, when the American Federation of Labor pulled together a bunch of smaller trade unions into one large force, sparking the first sustained American labor movement. In 1955, the AFL merged with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, forming the AFL-CIO. The acting union, SAG-AFTRA, has been affiliated with the AFL-CIO for over fifty years. The Writers Guild East (there are two different branches of the Writers Guild of America) has been associated with the AFL-CIO since 1989. This is a long-winded way of saying that my unions are an important part of the larger labor movement, which makes sense because writers and actors are craftspeople plying a trade. Our history is theirs.

Naturally, when people think of “Hollywood,” they think of the glitz and glamor. And to be fair, there is nothing more glamorous than hanging out on Hollywood and Vine watching pretend Spider-Men take photos with Japanese tourists. What they don’t think about are the long hours on set, the extended periods of unemployment, the occasionally hazardous working conditions. They don’t think about the financial realities for the vast majority of union members. SAG-AFTRA actors earn, on average, about $40,000. That’s not a lot of money. Union writers typically do much better, but their employment (like actors) is tenuous and prone to long periods of draught. With the advent of artificial intelligence, the ability of both writers and actors to earn a living at all is in jeopardy. For most of us in either union, Hollywood is much more akin to a factory town than to some kind of spotlit Xanadu. It’s a place where tradespeople go to ply their trade, and hopefully make a decent living doing so. Very few of us ever strike it rich or even achieve the kind of financial stability that would make union membership unnecessary.

The film and television industry doesn’t just support itself. Our efforts put money into a lot of people’s pockets. In fact, according to the Motion Picture Association, “The American film and television industry supports 2.4 million jobs, pays out $186 billion in total wages, and comprises more than 122,000 businesses.” These businesses are often small mom-and-pop places all over the country that film productions while on location. For example, according to the MPAA again:

When a movie or television show shoots on location, it brings jobs, revenue, and related infrastructure development, providing an immediate boost to the local economy. Our industry pays out $21 billion per year to more than 260,000 businesses in cities and small towns across the country—and the industry itself is comprised of more than 122,000 businesses, 92 percent of which employ fewer than 10 people. As much as $250,000 can be injected into local economies per day when a film shoots on location. In some cases, popular films and television shows can also boost tourism.

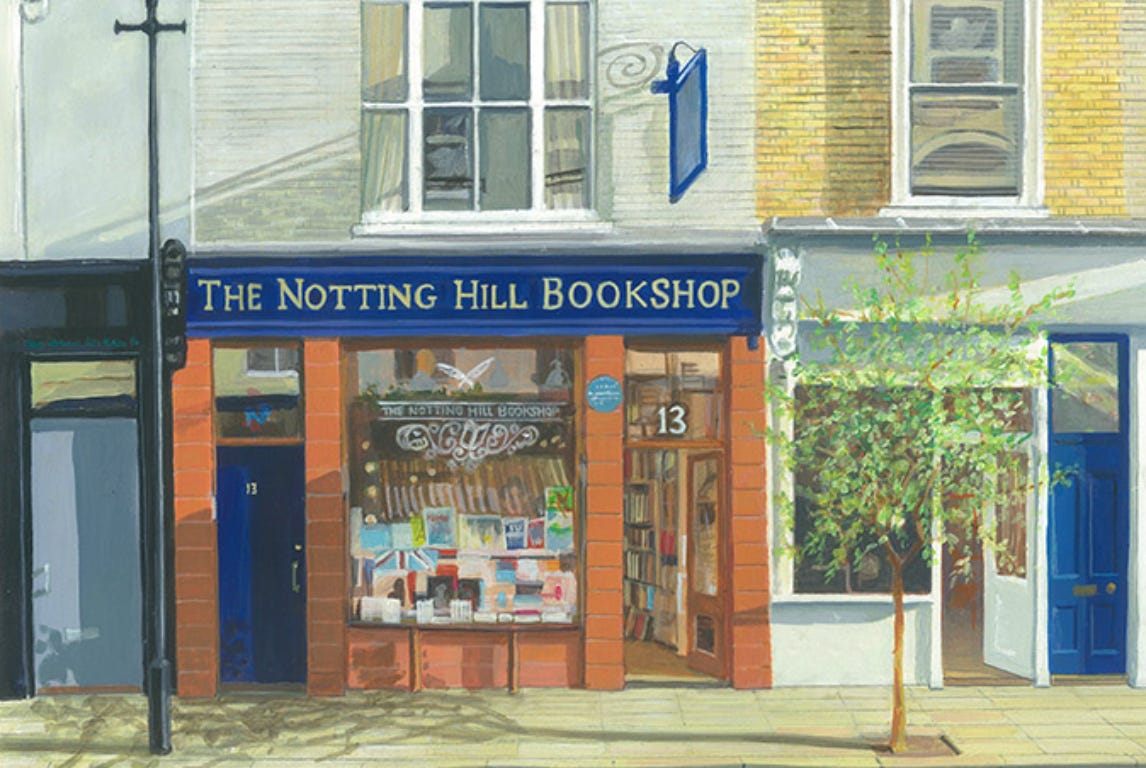

Case in point regarding a popular film boosting tourism: recently, I was on the hunt for a book. I Googled “bookshops near me” and found one about a twenty minute walk from the flat in which I’m staying in London. When I got there, the place was mobbed. Whoever heard of a mobbed bookstore? As it turns out, this was the Notting Hill Bookshop, made famous by the 1999 Julia Roberts/Hugh Grant romantic comedy Notting Hill. That movie came out almost 25 years ago and the featured bookshop is still reaping the benefits. In this case, what’s good for the goose really is good for the gander! Furthermore, I have no idea what a gander is.

We rely on our unions to protect our interests, the same way auto workers and pipefitters do. It’s our unions that gave us residuals, health insurance, good safety conditions, pensions so we can retire with dignity, and the most important benefit: free movie screeners during awards season. Without our unions, we’re no different than Our Gang putting on a show in Darla’s barn. (As an aside, I grew up watching the Our Gang shorts, which aired all the time on Saturday mornings decades after they were made. The casts of those shorts ever received a dime of residuals because they were made before unions forced the studios to pay them. Also, as an aside to an aside, Alfalfa was shot to death when he was 31 for reasons totally unrelated to anything involving show biz.)

Personally, one of the proudest moments of my professional career was the day I qualified to join SAG (this was before it merged with AFTRA). Maybe it sounds hokey, but I remember holding my union card for the first time and feeling real pride and a connection to the thousands of actors who came before me, including “Michael Black”, an actor who has exactly three credits to his name and who, because of union rules preventing actors from sharing a name to prevent confusion, forced me to inject my middle name into my professional name. That Michael Black, who played “dancer” in 1984’s Gimme an F, is entitled to the same union protections as myself and all the rest of us. He’s as important a member as the ones whose names you see in lights.

It was acting that got me into writing and it’s writing that sustains my acting. Both unions are integral to my life and I’m proud to be a member of both. I’m also so happy that I’m living in Europe right now so I don’t have to put on my striking sneakers and hit the picket lines with my comrades. Yes we need to strike to protect our livelihoods but I don’t want to have to work up a sweat about it. For God’s sake, avoiding sweating is why I got into the arts in the first place.

¡Viva la Revolución!

"The casts of those shorts ever received a dime "

You might enjoy Keith Olebermann's Friday Countdown podcast. He devotes most of the second act to describing life in LA and the strike. Also, on Fridays he reads a short story by James Thurber which are pretty good.

I canceled all my streaming services yesterday and subscribed here today. Honestly, eff me for not doing that to begin with. I'm too busy being a cog in Meta's content machine to watch anything anymore anyway. But I was disappointed that at the end of every cancel screen, I was never offered the option to select "I don't want my fellow creative workers out on the streets."

I won't blame you if you and Martha never come back.